Creative Technologist.

Current MDes Mediums Student at the GSD.

Contact me

You can reach me at

alexiaasgari@gmail.com

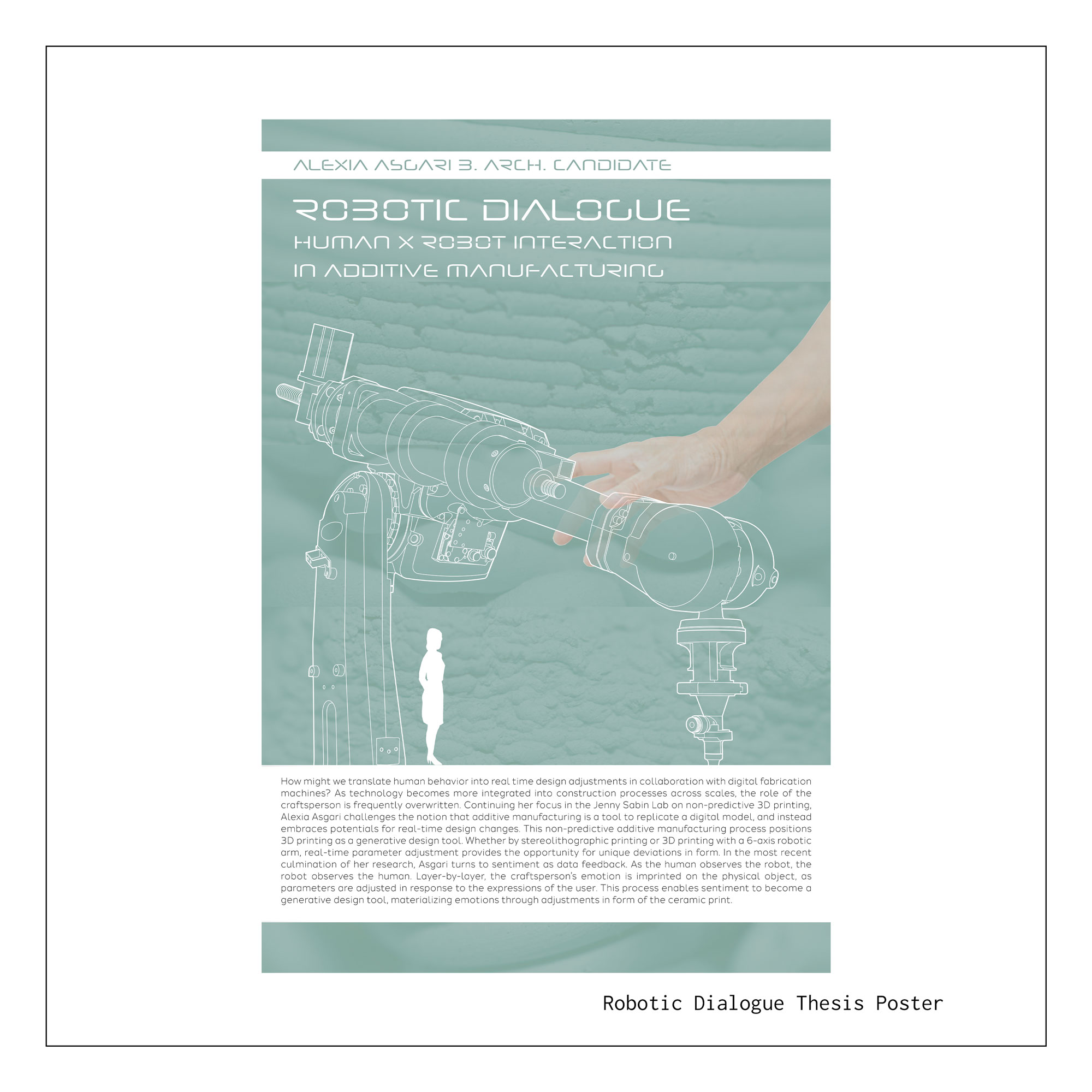

Human X Robot Interaction in Additive Manufacturing

Spring 2022 | Advisors Professor Jenny Sabin and Professor David Costanza

"How might we translate human behavior into real time design adjustments in collaboration with digital fabrication machines? As technology becomes more integrated into construction processes across scales, the role of the craftsperson is frequently overwritten. Continuing her focus in the Jenny Sabin Lab on non-predictive 3D printing, Alexia Asgari challenges the notion that additive manufacturing is a tool to replicate a digital model, and instead embraces potentials for real-time design changes. This non-predictive additive manufacturing process positions 3D printing as a generative design tool. Whether by stereolithographic printing or 3D printing with a 6-axis robotic arm, real-time parameter adjustment provides the opportunity for unique deviations in form. In the most recent culmination of her research, Asgari turns to sentiment as data feedback. As the human observes the robot, the robot observes the human. Layer-by-layer, the craftsperson’s emotion is imprinted on the physical object, as parameters are adjusted in response to the expressions of the user. This process enables sentiment to become a generative design tool, materializing emotions through adjustments in form of the ceramic print."

My passion for non-predictive fabrication culminated in my undergraduate thesis combining interests in cognitive science, design, and technology. This research was presented at the Rawlings Research Scholars Senior Expo and was featured in an article in the Cornell Research Journal (which can be accessed by clicking here).

How might we translate varying human sentiment into real-time adjustments for non-predictive design through ceramic 3D printing?

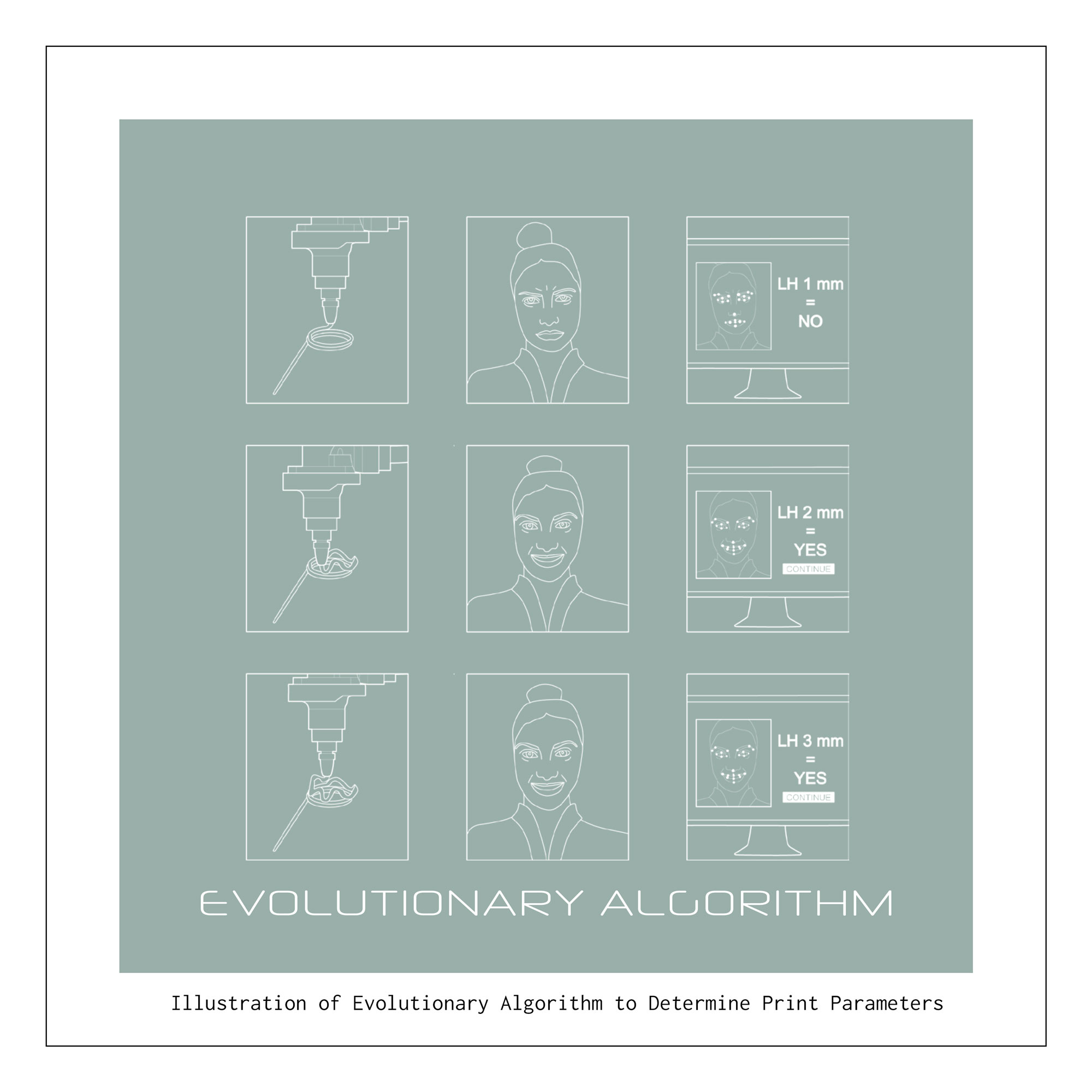

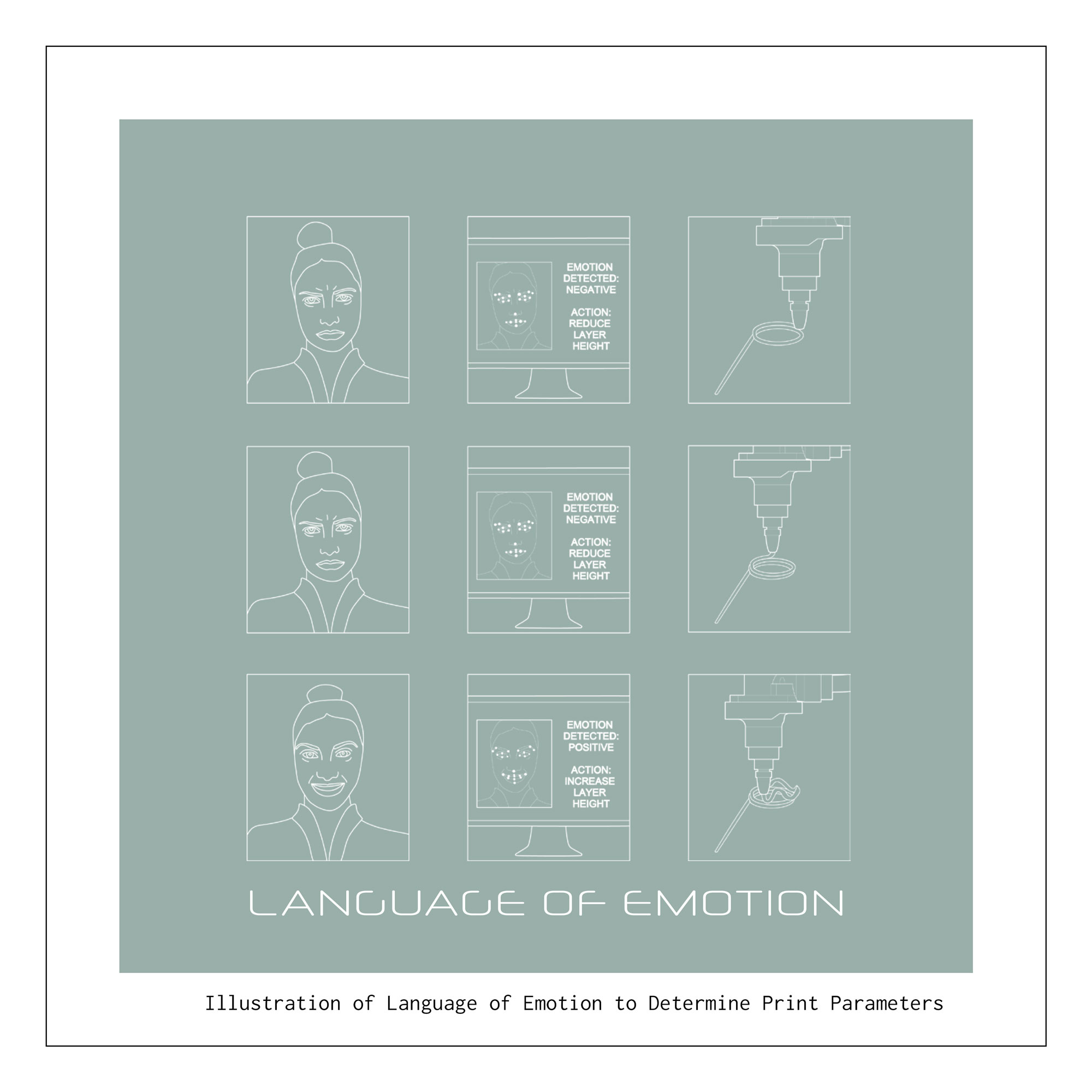

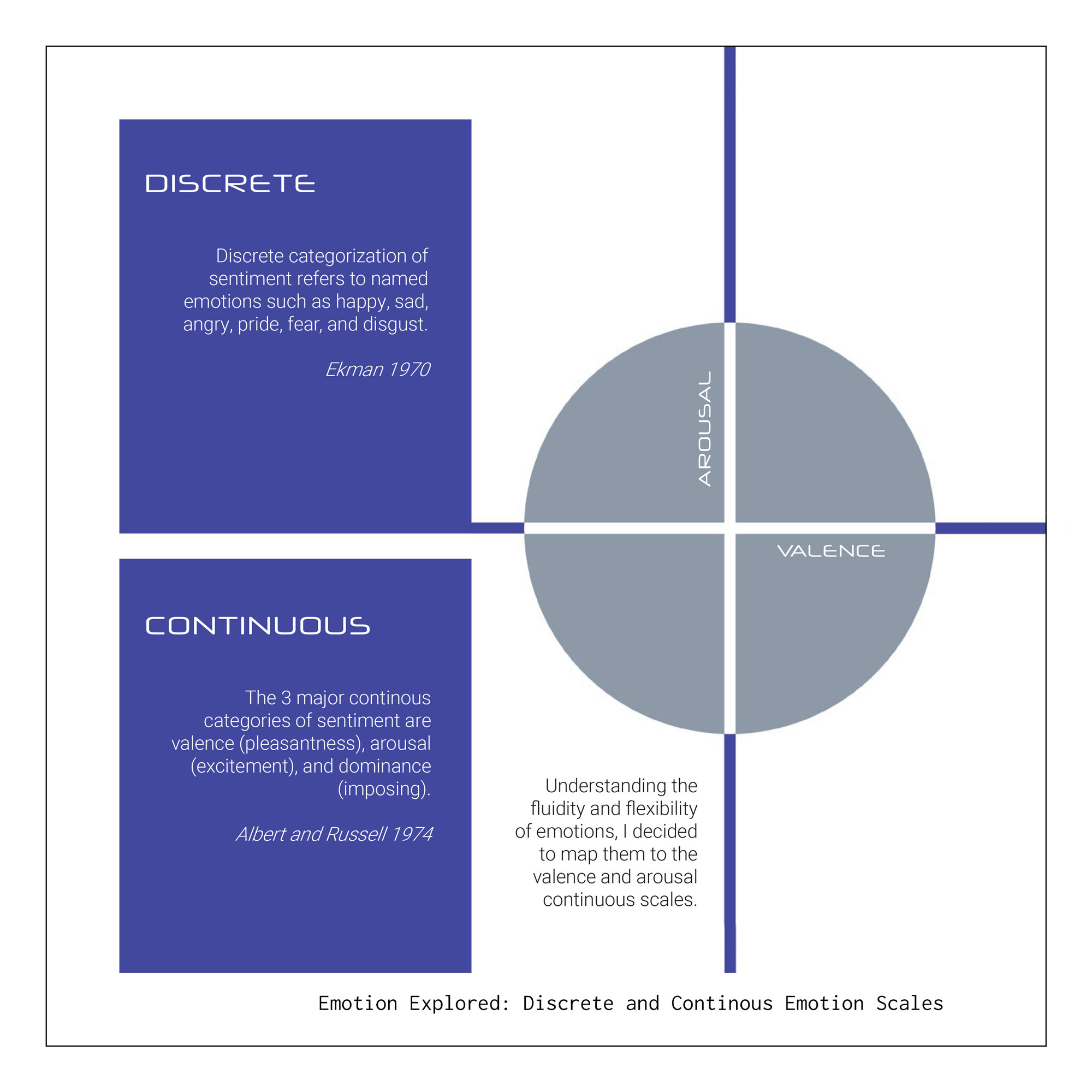

There were two potential strategies for the print: using an evolutionary algorithm where positive expressions would be designated as “yes” answers and negative expressions as “no” answers, or creating a language of emotion where each emotion is assigned its own specific parameter adjustment in response. While I was initially interested in the potential of an evolutionary algorithm to learn the individual design style of each user, layer by layer producing prints that received more positive feedback, time restrictions meant developing a language of emotion would be the best strategy for the time being. I used research to determine how I would correlate emotions to specific responses.

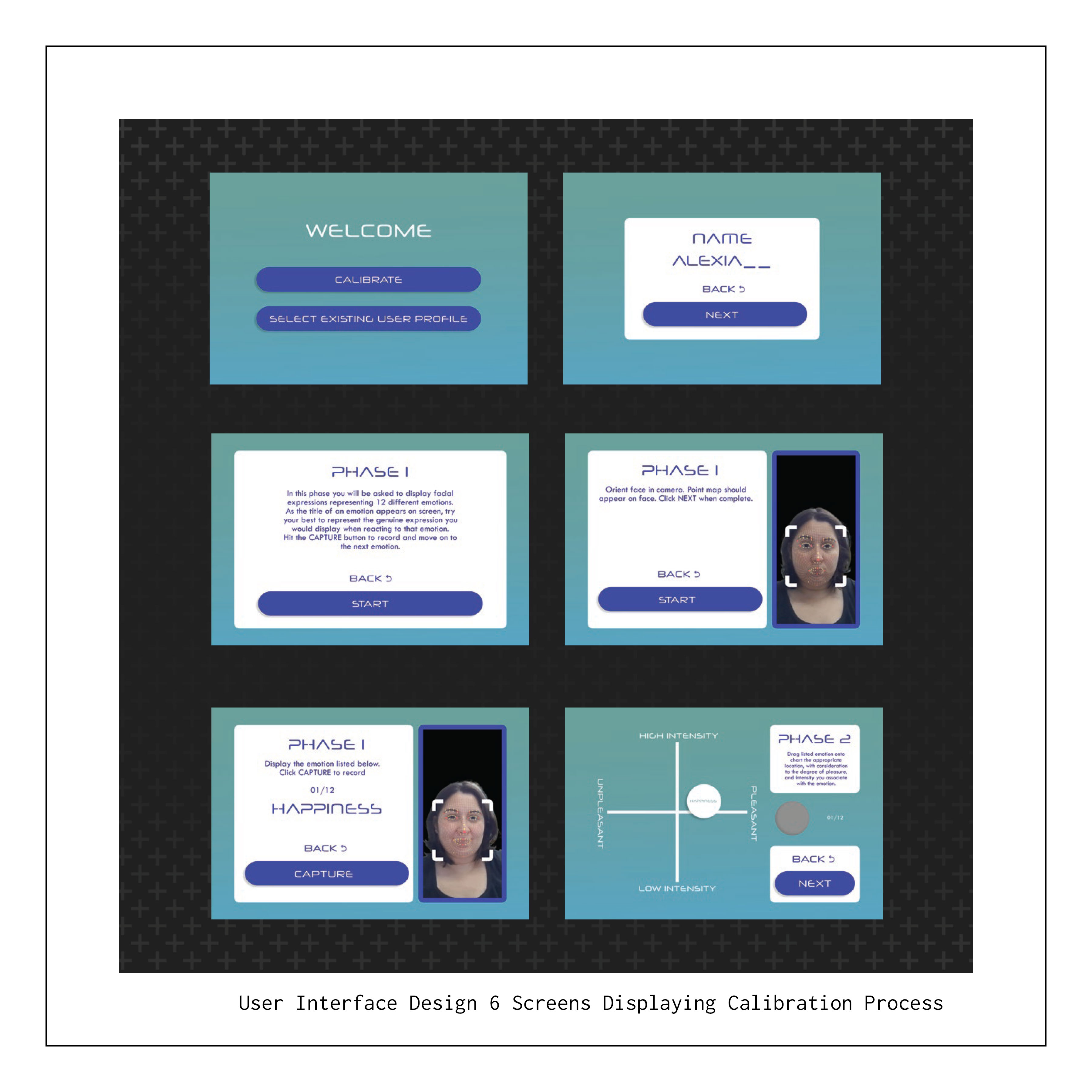

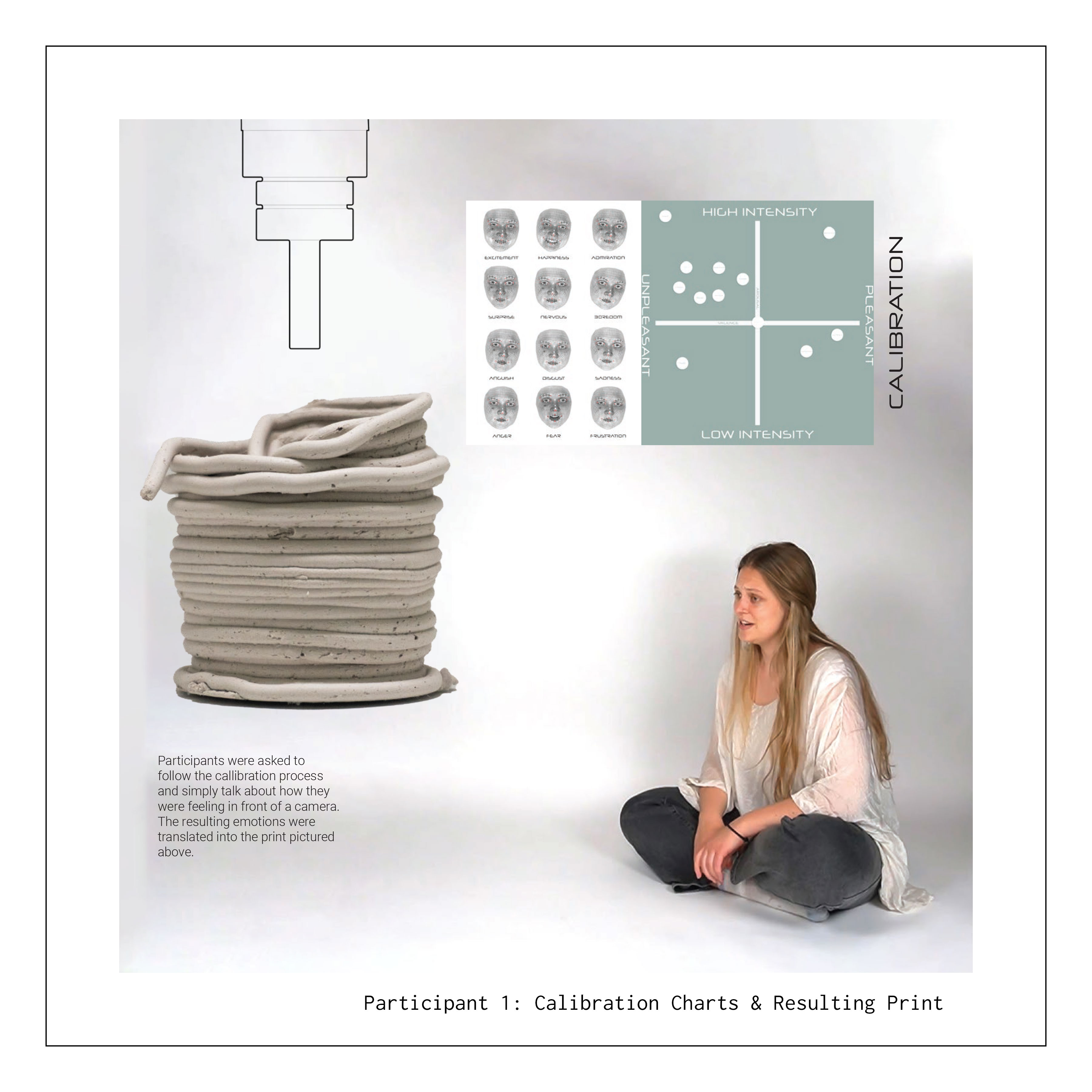

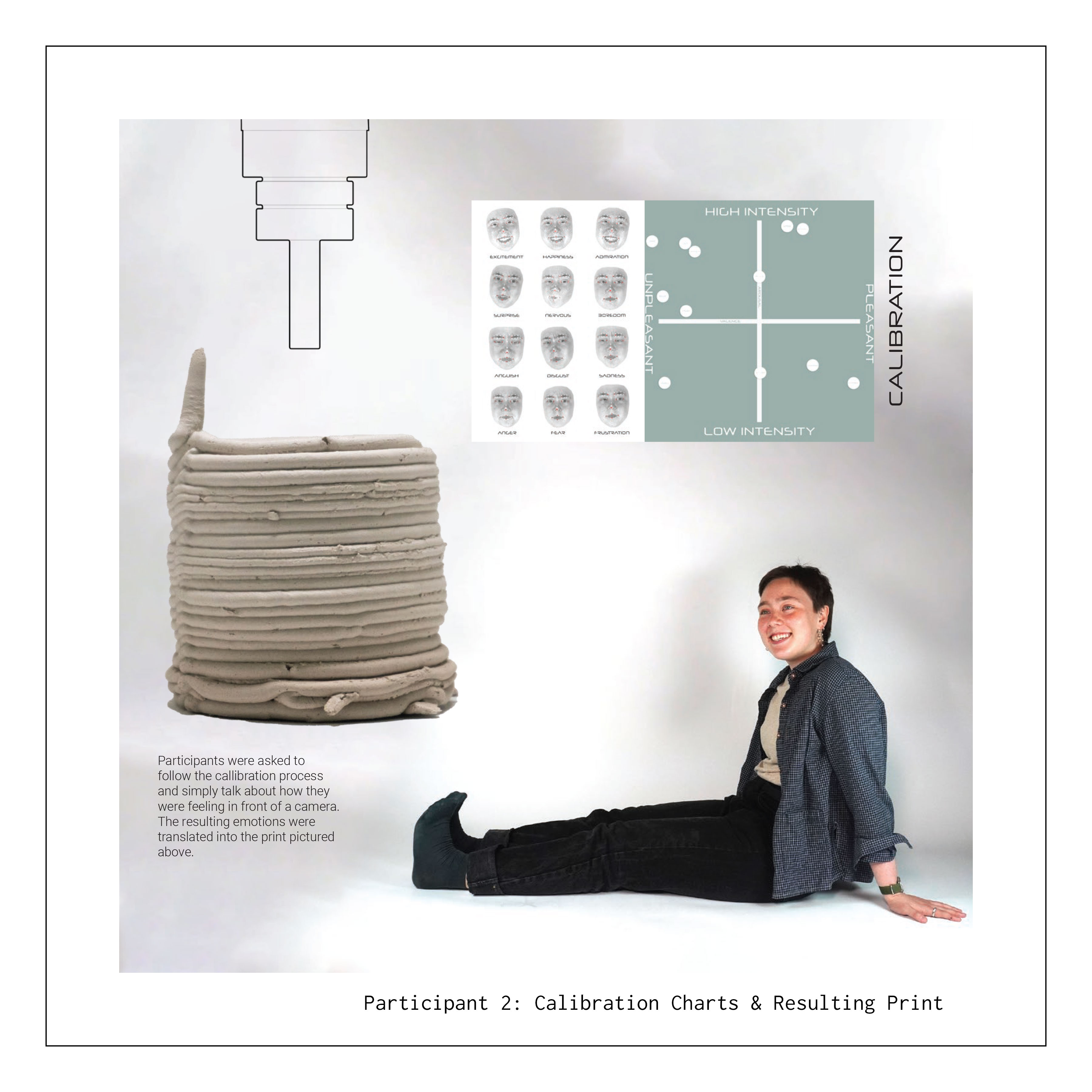

In an effort to gain a wide perspective on how to quantify emotion, I conducted several surveys connecting with designers, non-designers, and multicultural communities. These surveys highlighted the need for a calibration process with emotional expression being highly personal.

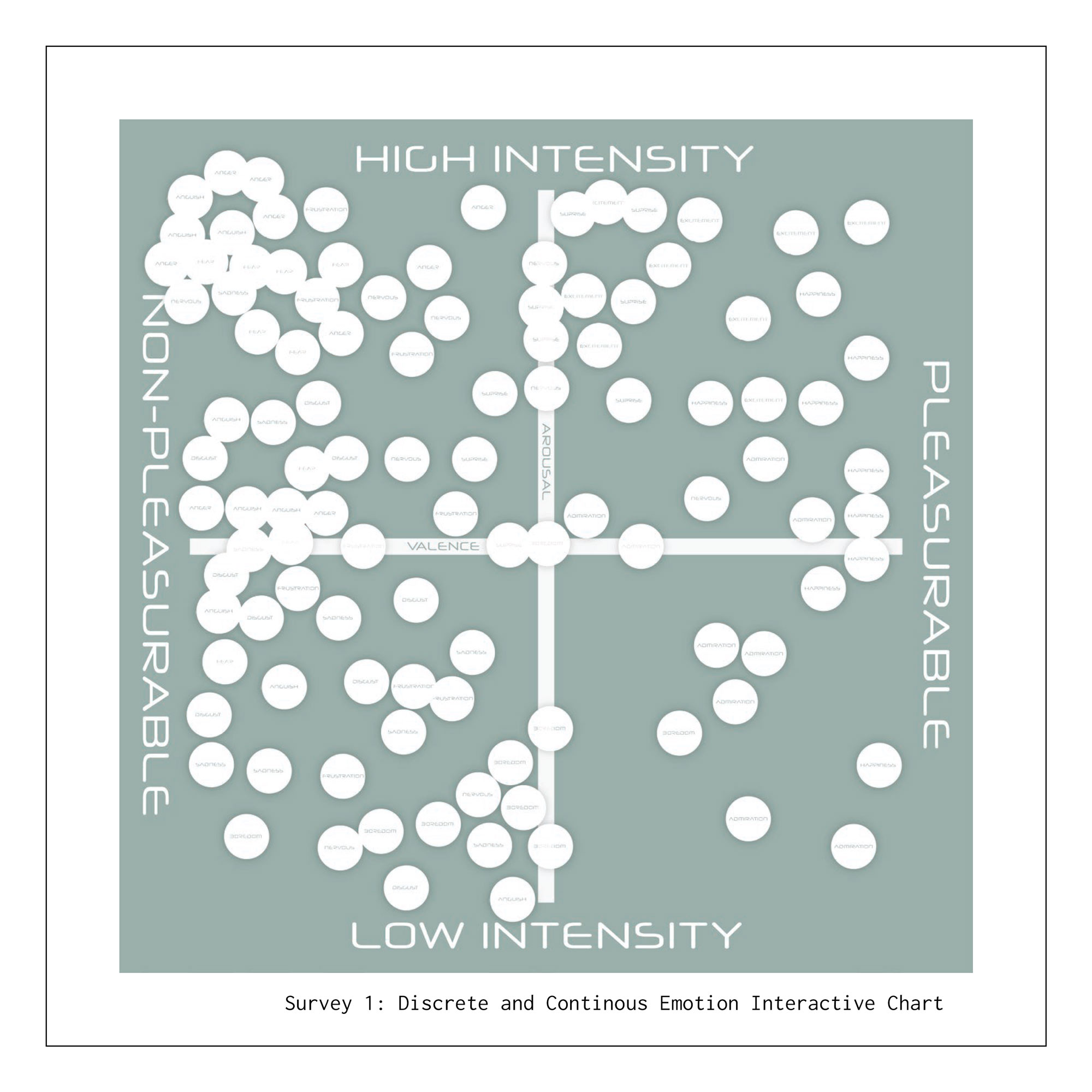

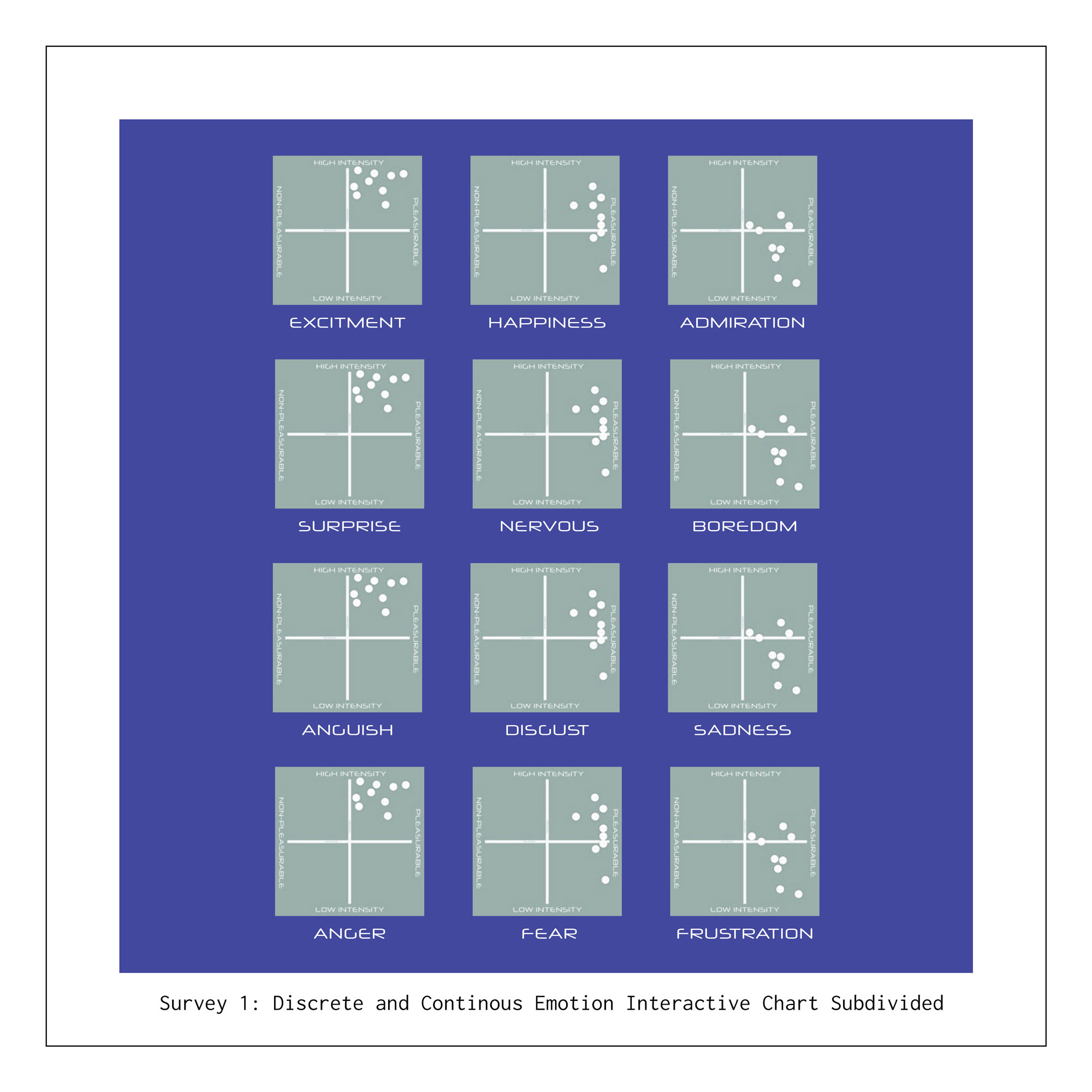

Survey 1

Discrete and Continuous Emotions Interactive Chart

Survey 1 provided participants with a set of stickers, asking them to place the emotion stickers on the chart, wherever they saw fit. Later individual emotion stickers were separately noted for comparison.

Survey 2

Emotion Detection Questionnaire

In Survey 2, participants were shown a series of photos and asked to identify the emotions pictured and other questions surrounding sentiment.

Takeaways:

Interpersonal facial sentiment detection without context can be just as challenging for humans as automated systems. With more photos of the same person, the answers became more precise. However, in sets of photos of different people, answers remained varied, pointing to the individuality of emotional expression. There is a need to see people in other contexts for both humans and robots, pointing to the necessity of a calibration process when printing.

The survey can be found by clicking here

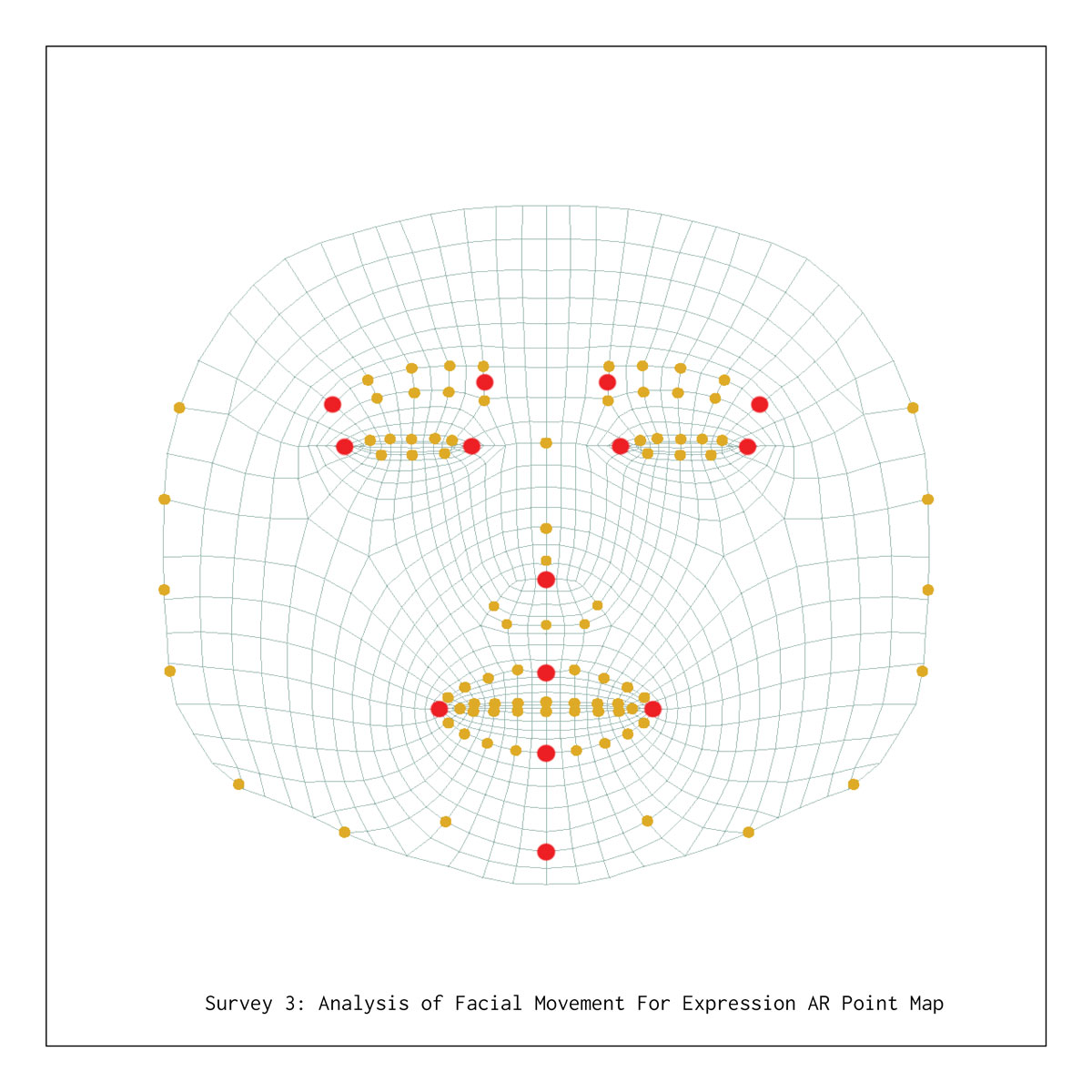

Survey 3

Analysis of Facial Movement For Emotional Expression

In Survey 3, participants were asked to replicate how they express each of 12 listed emotions. Using augmented reality, a point map was applied to the face of each user, allowing the movements of key facial features to be recorded and compared between expressions.

Takeaways:

Again emotion is proved to be very individual. While some tendencies like thinning of the lower lip convey nervousness, and raised eyebrows are generally associated with high intensity emotions, most differences are very subtle between similar emotions. Again calibration is required for each user to customize it to their sentiment expression.

Survey 4

Form and Sentiment Interactive Chart

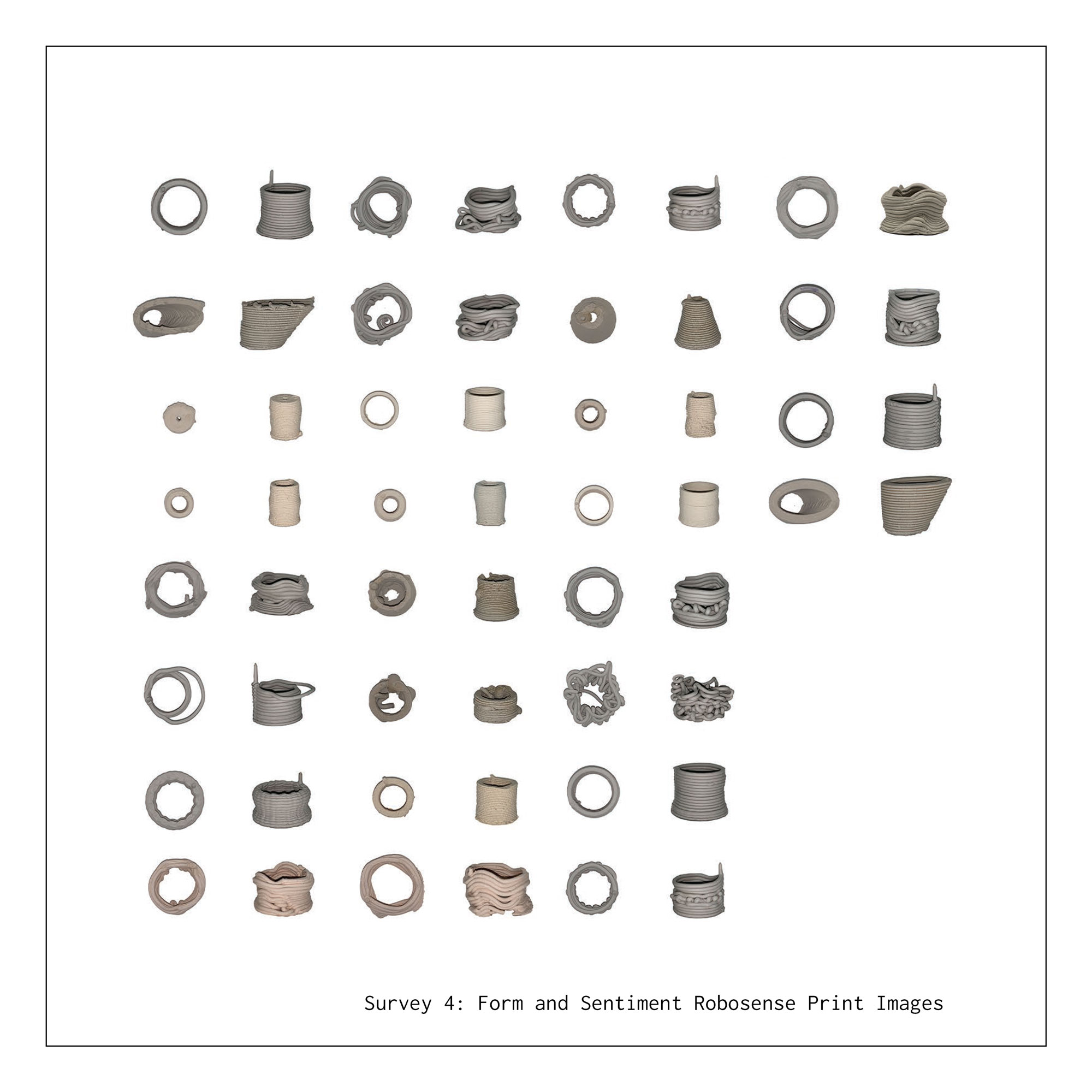

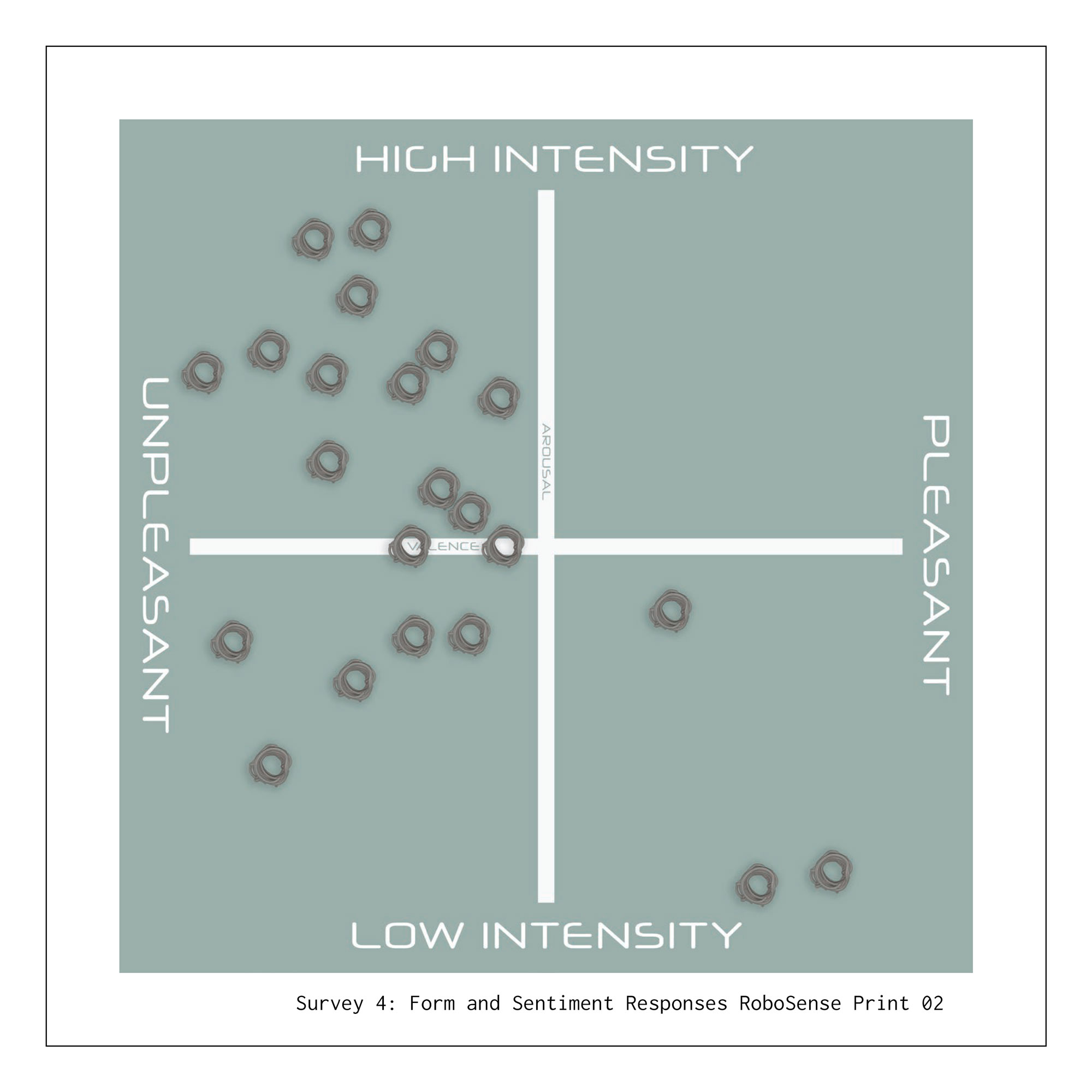

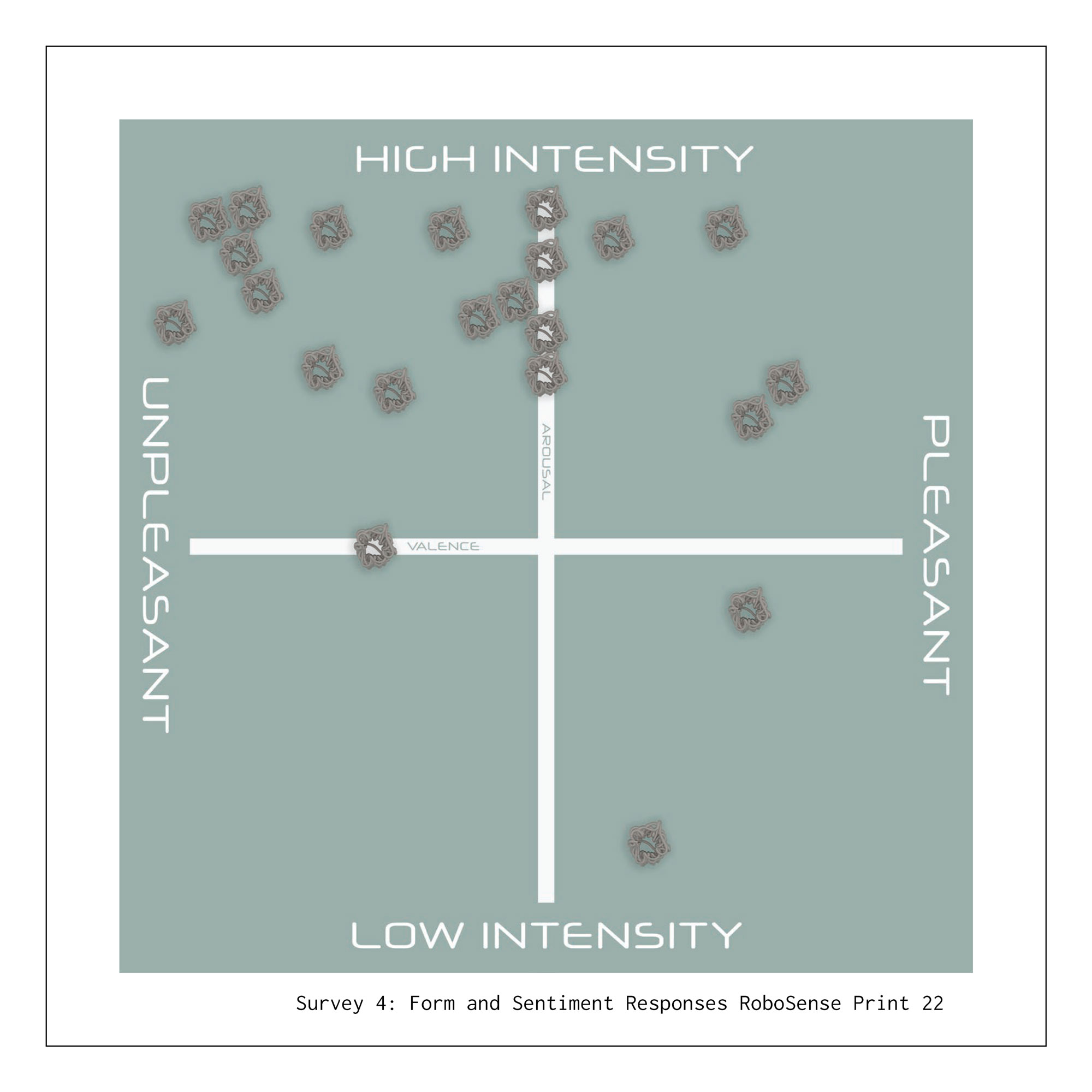

Survey 4 was unique in that it exclusively targeted designers for responses. Here participants were given images of prints produced by the Robosense Team in plan and section view (pictured above). Each print featured a cylindrical toolpath whose profile was altered through the use of print parameters. Participants were asked to talk through their reasoning for their placements on the arousal/valence scales (pictured on the right), with some pointing out irregular patterns being less pleasant, and sharper turns being less pleasant. Objects similar to the parent form were generally viewed as low intensity. Combining multiple participant responses of the same print (pictured below) allowed trends to surface, such as higher layer height being viewed as generally more pleasant.

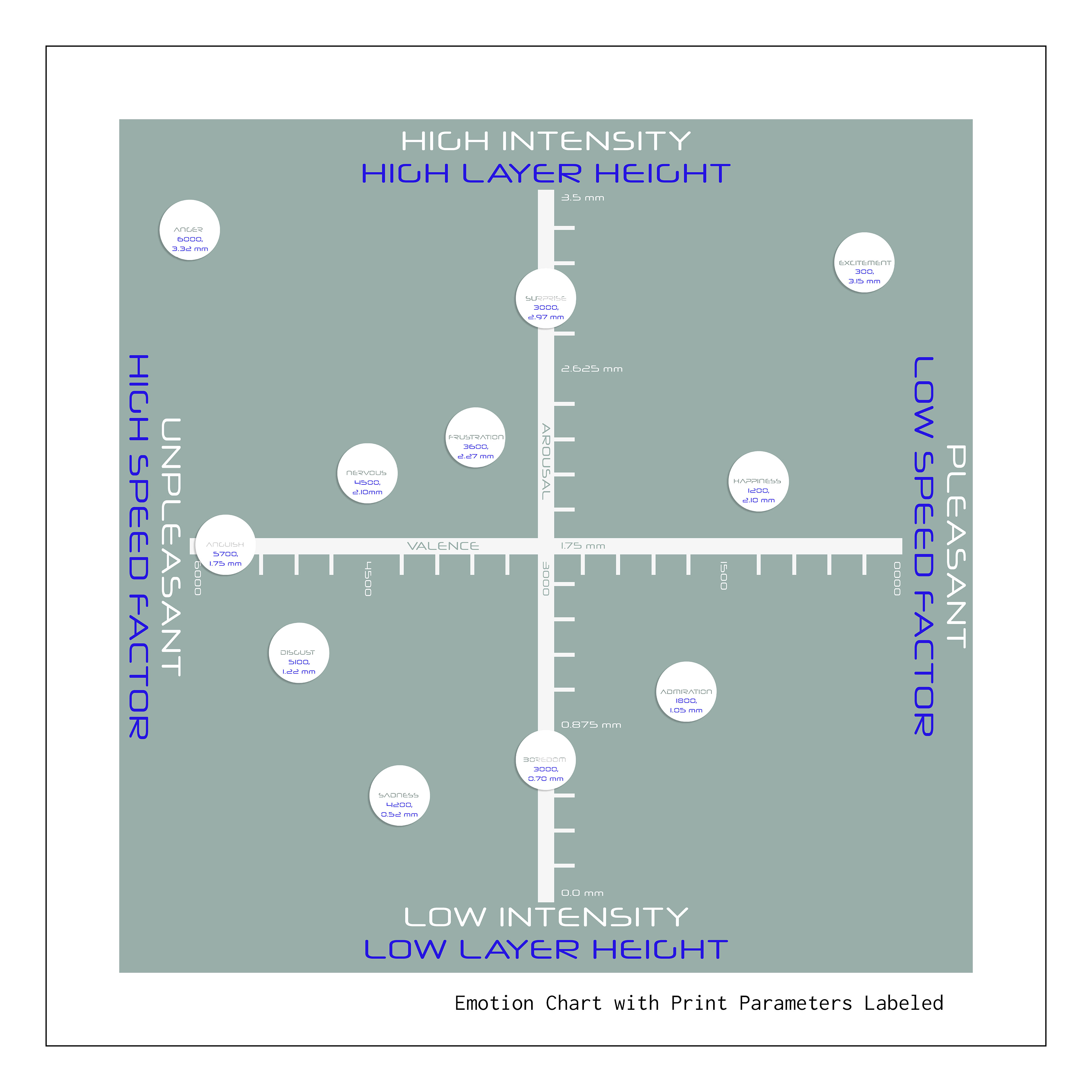

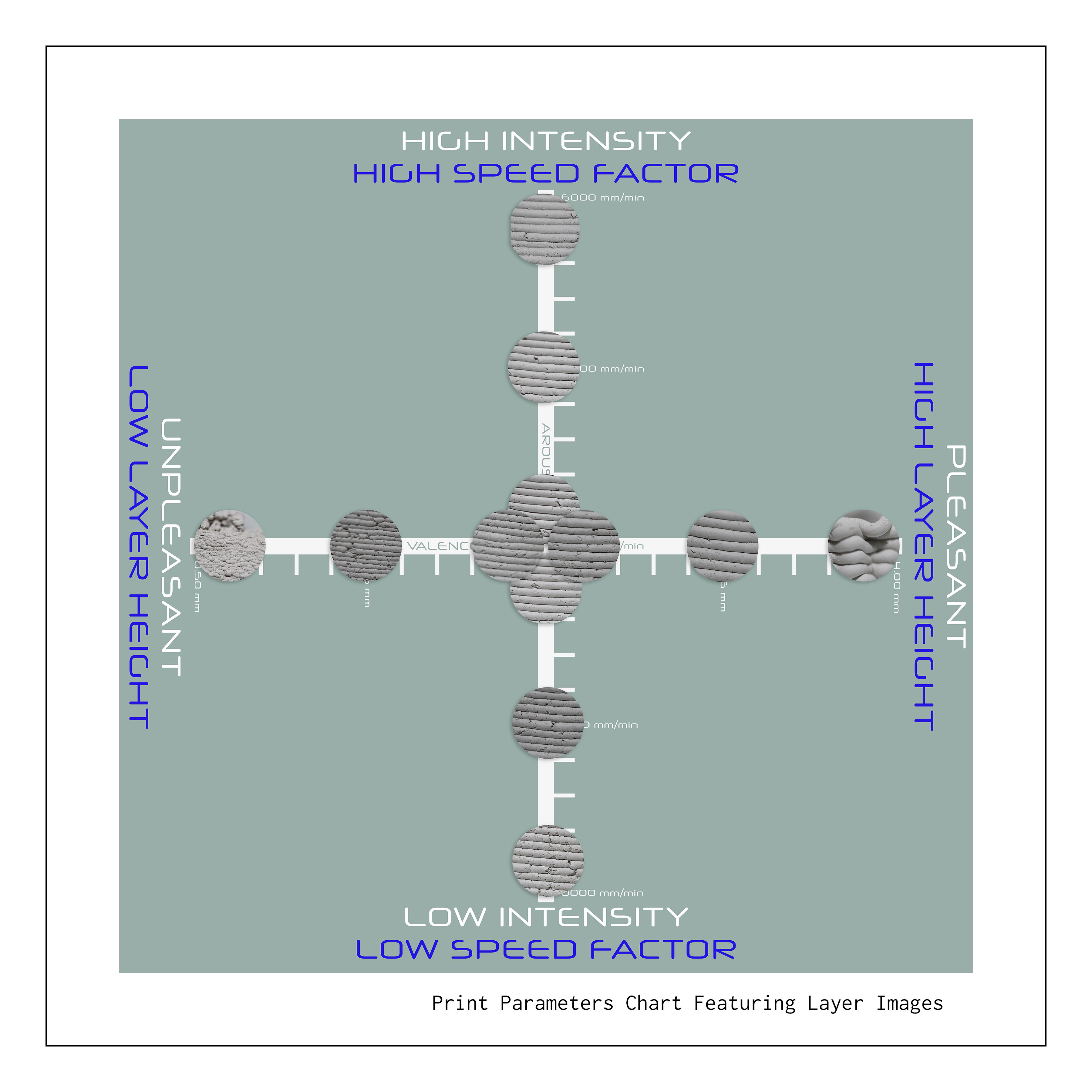

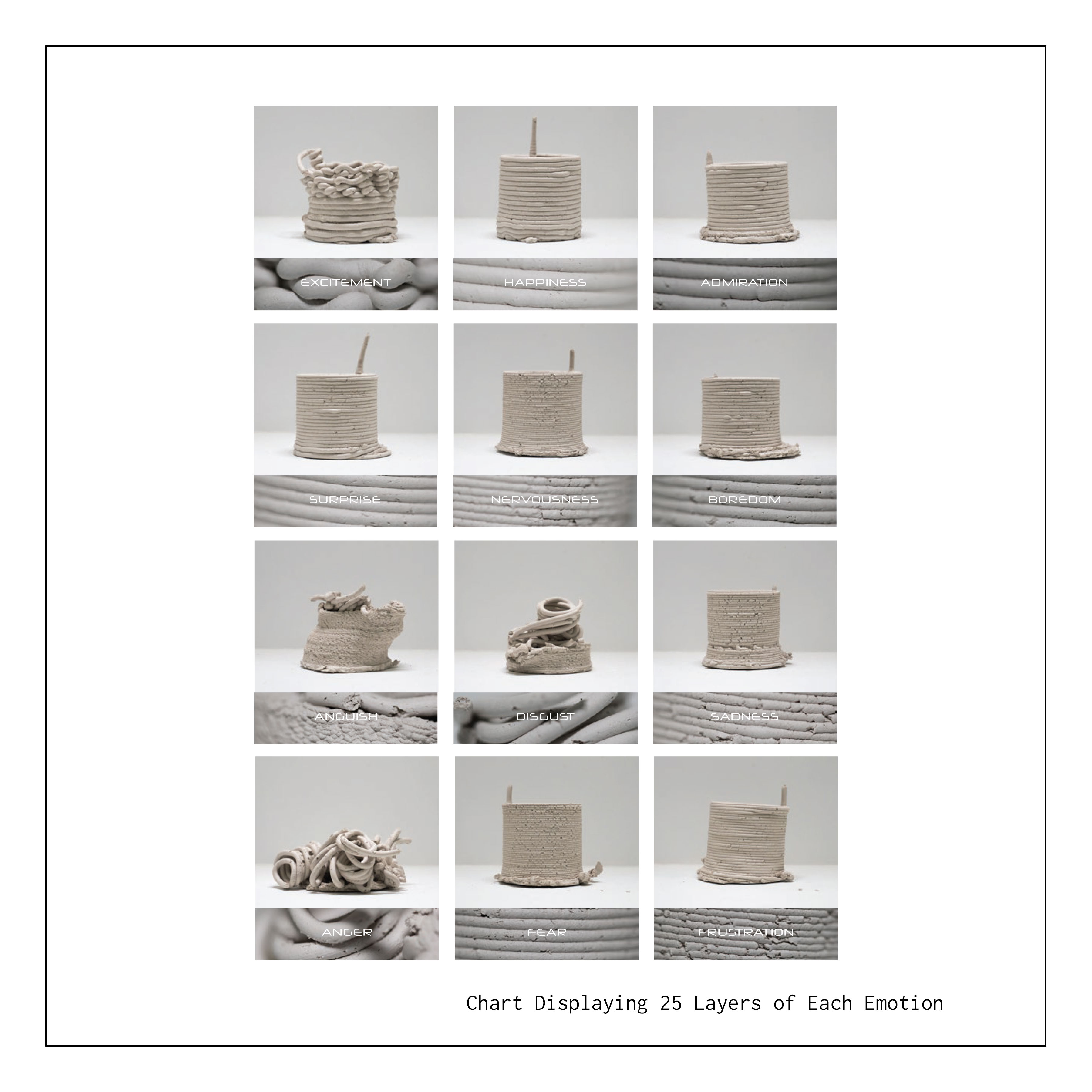

Using my own discrete emotion placements from Survey 1, I applied coordinates to these specific emotions. Due to findings from Survey 4, intensity was positively correlated to the speed factor parameter, and valence was correlated to the layer height parameter. The center of the chart would be the setting most likely to print the parent object as pictured digitally. The extent of the chart is determined by the limits of printability.

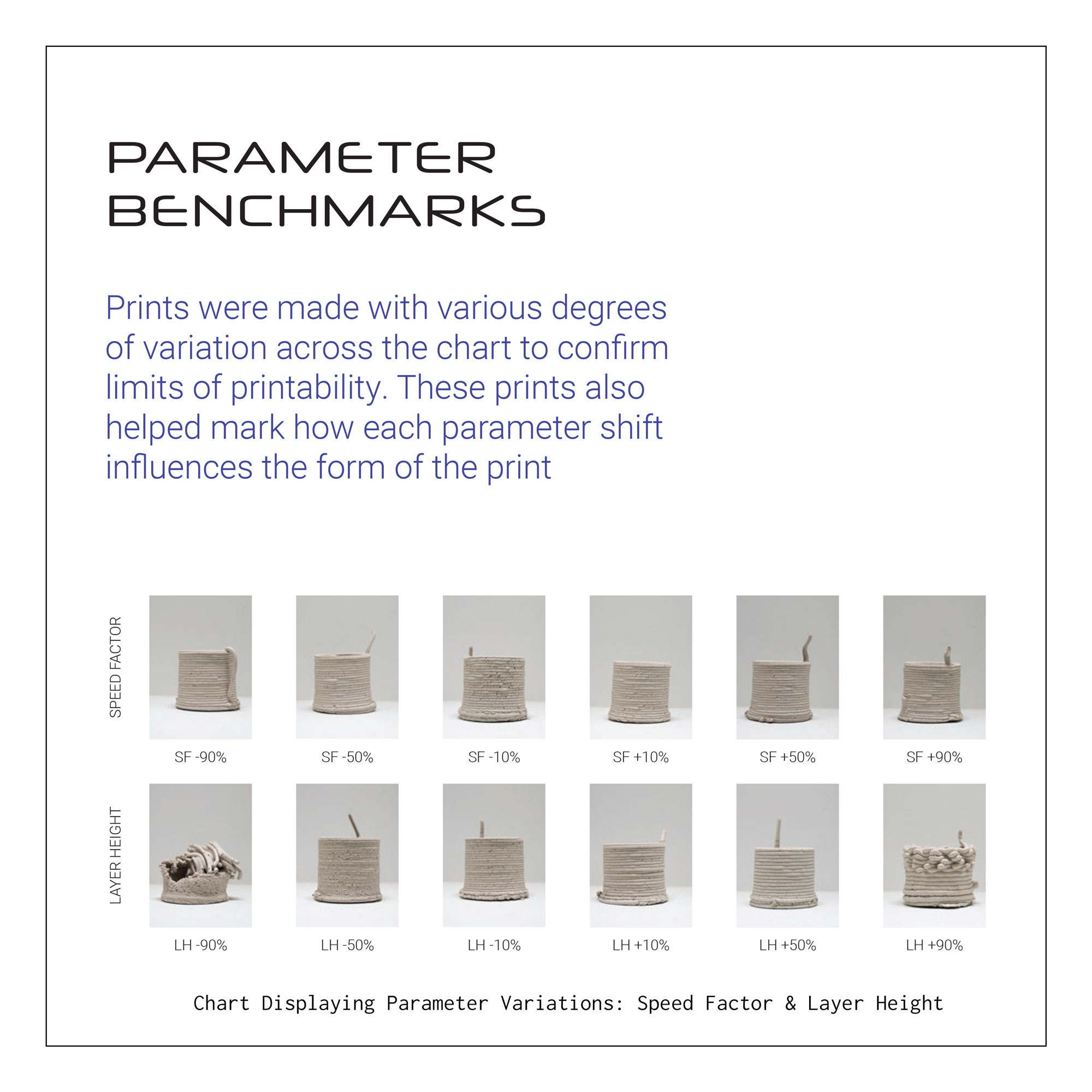

Prints were produced with various degrees of variation across the chart to confirm limits of printability. These prints also helped mark how each parameter shift influences the form of the print.

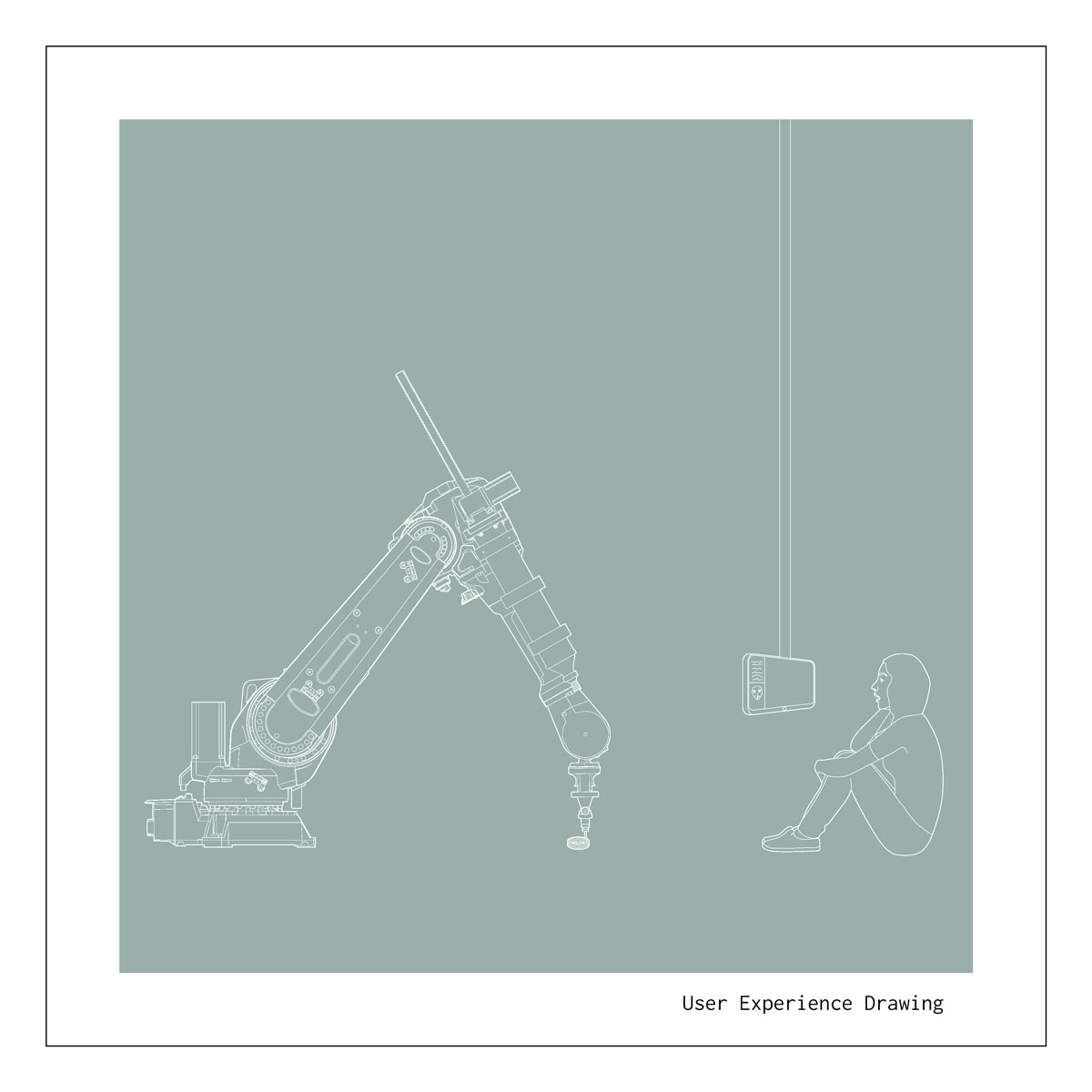

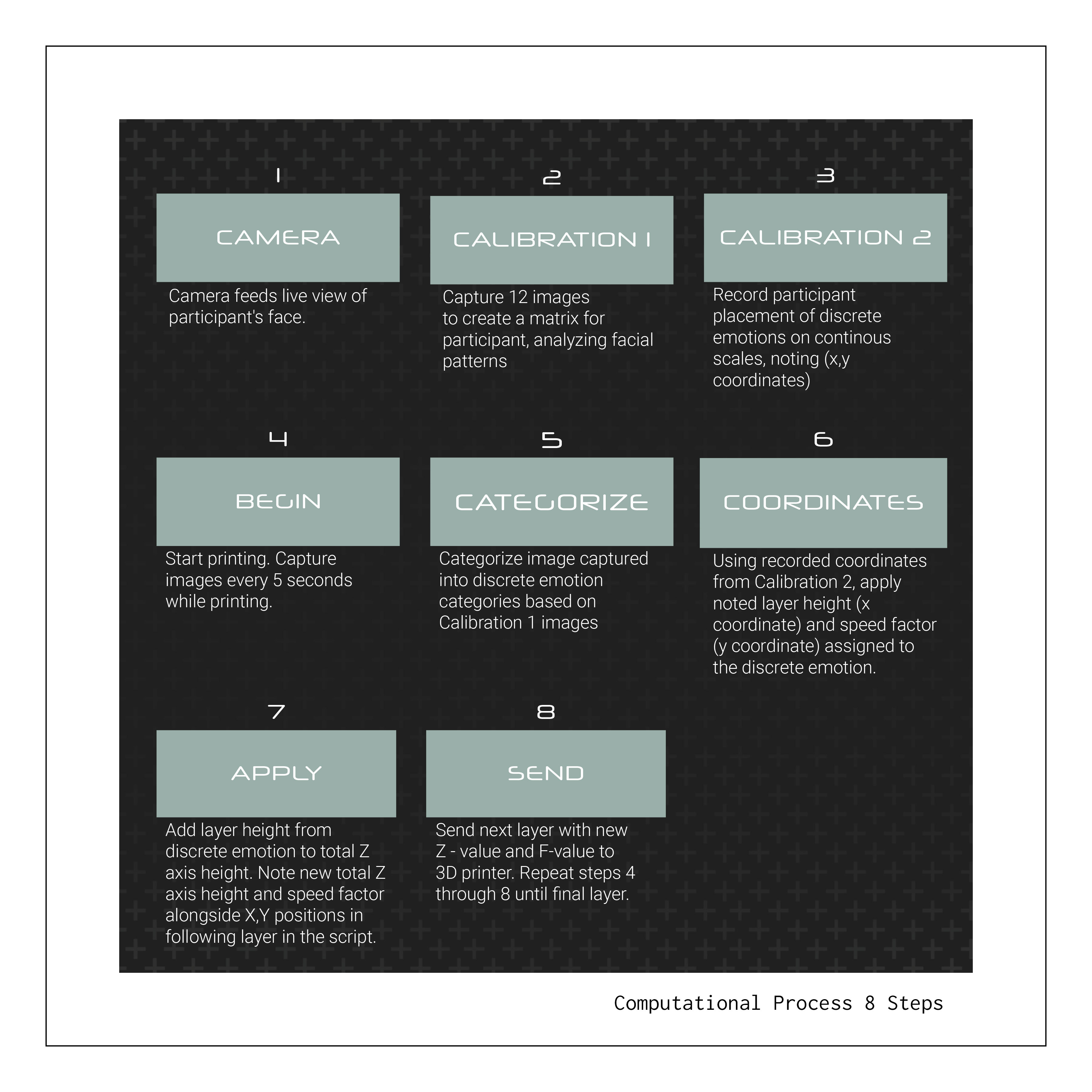

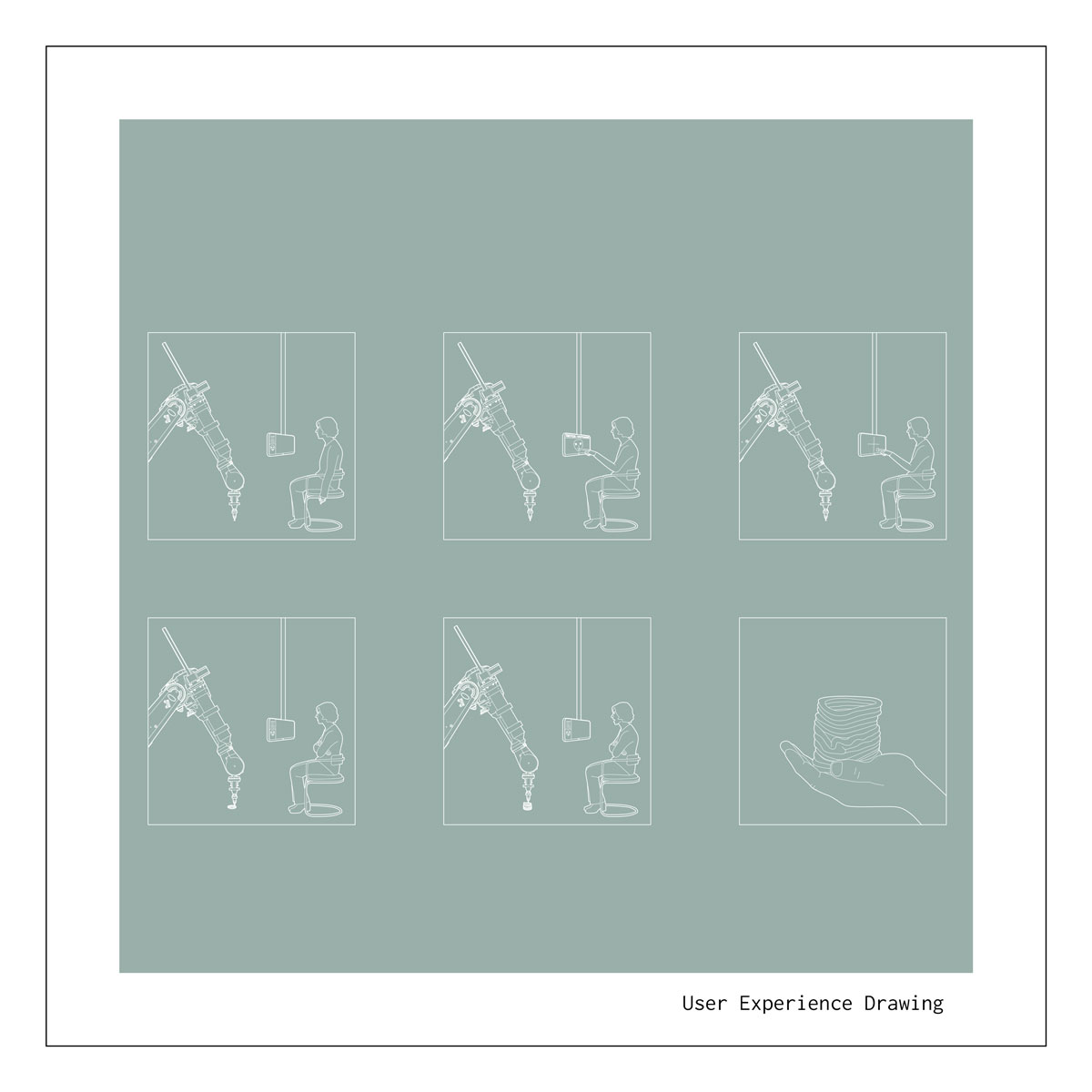

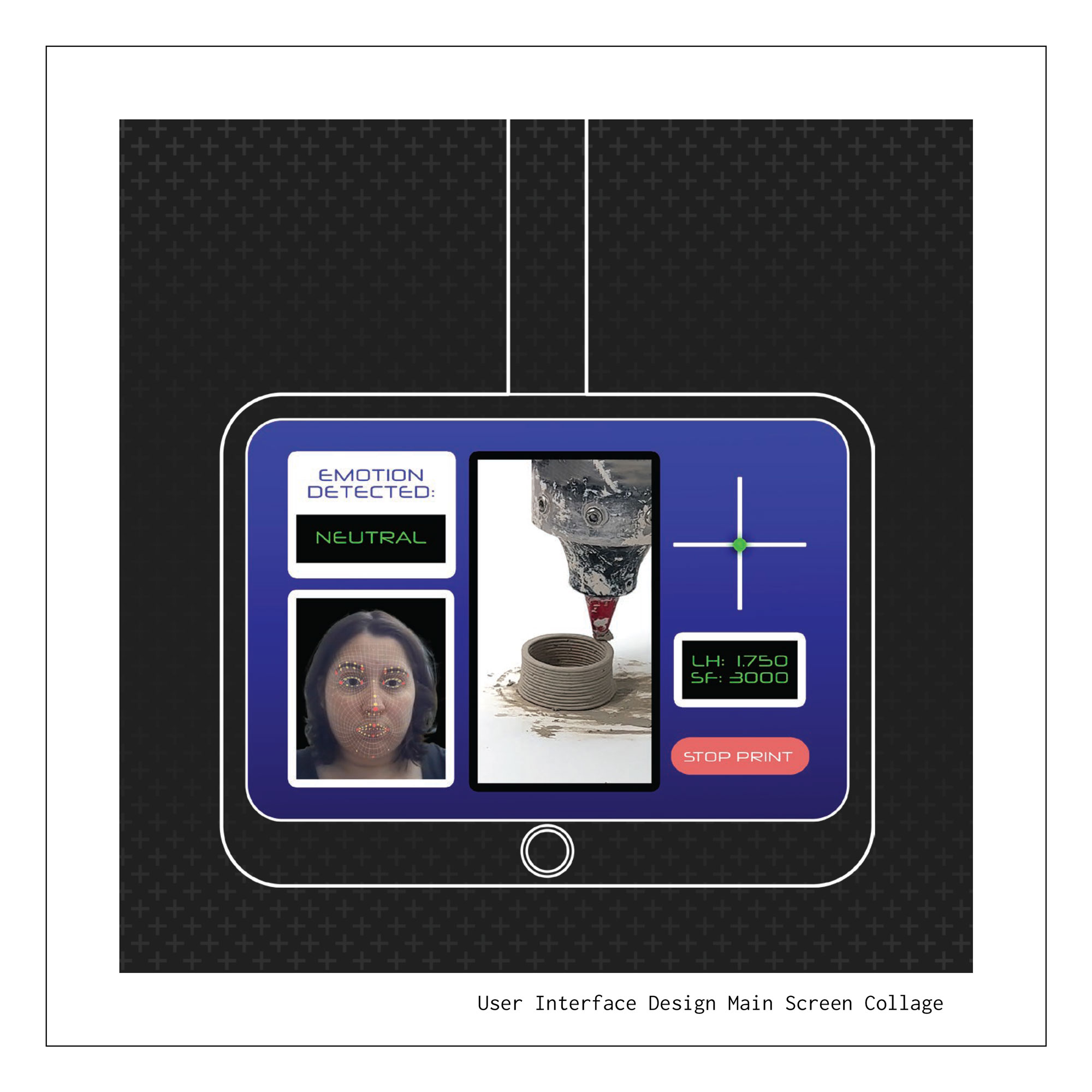

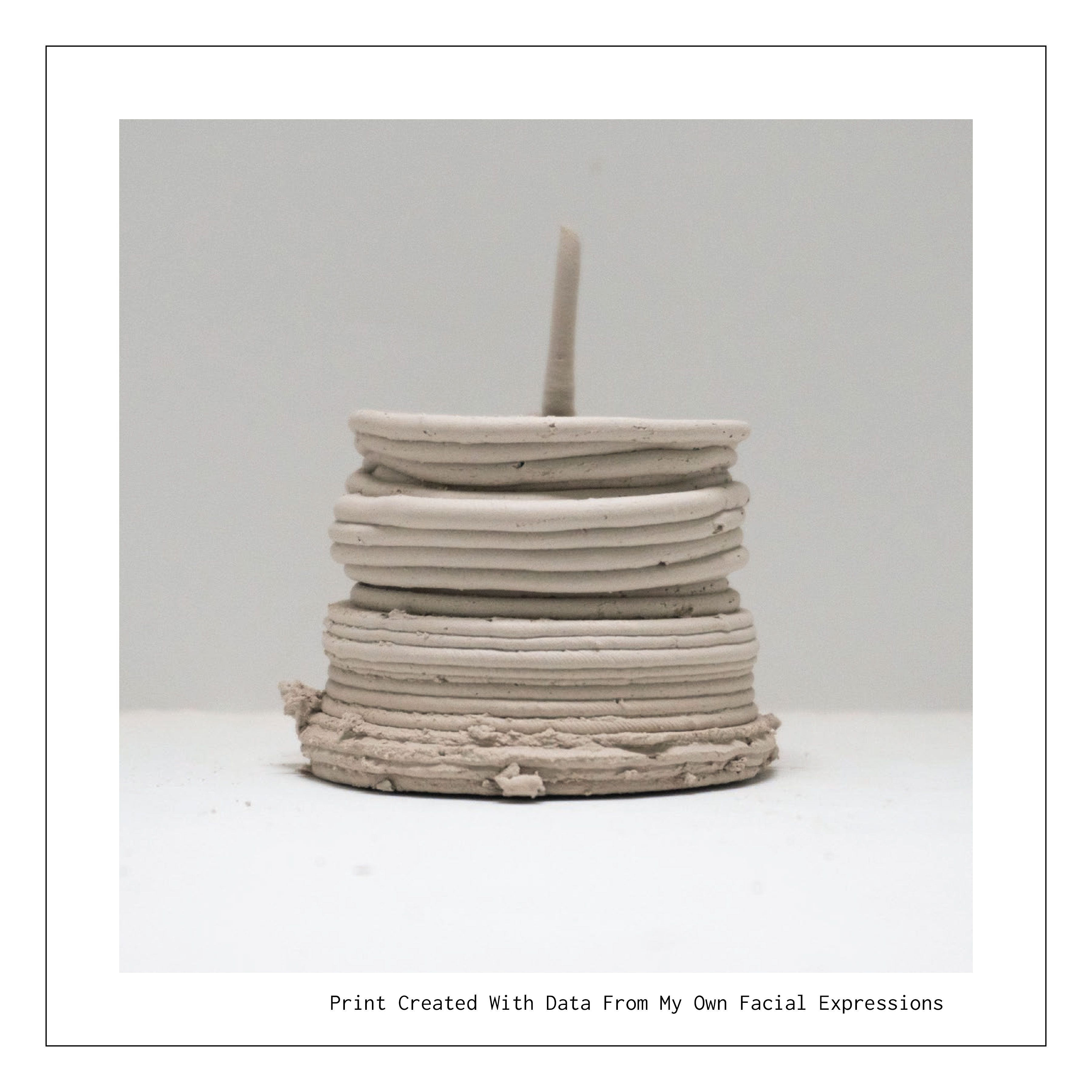

In order to create this system, a created a script (C#, grasshopper, and Java in SparkAR) that produced G-code based on real time communication or video input of a human face. I sat users in front of the camera asking them to discuss their day, allowing them to tell a variety of stories and exhibit a range of emotions. Though not implemented due to time constraints I created a potential user interface design for the system that would allow both computational proficient designers and casual users to utilize the program easily and intuitively.

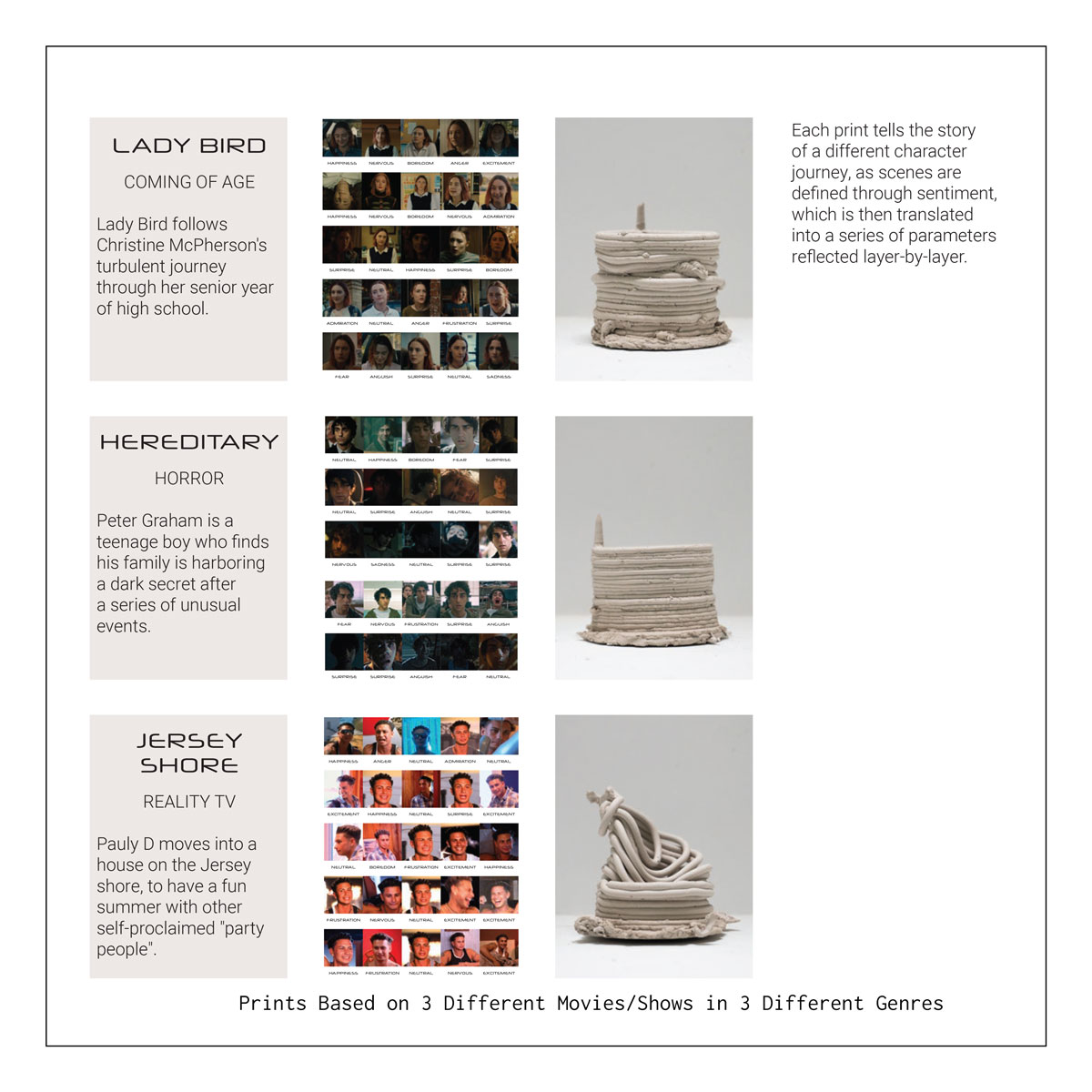

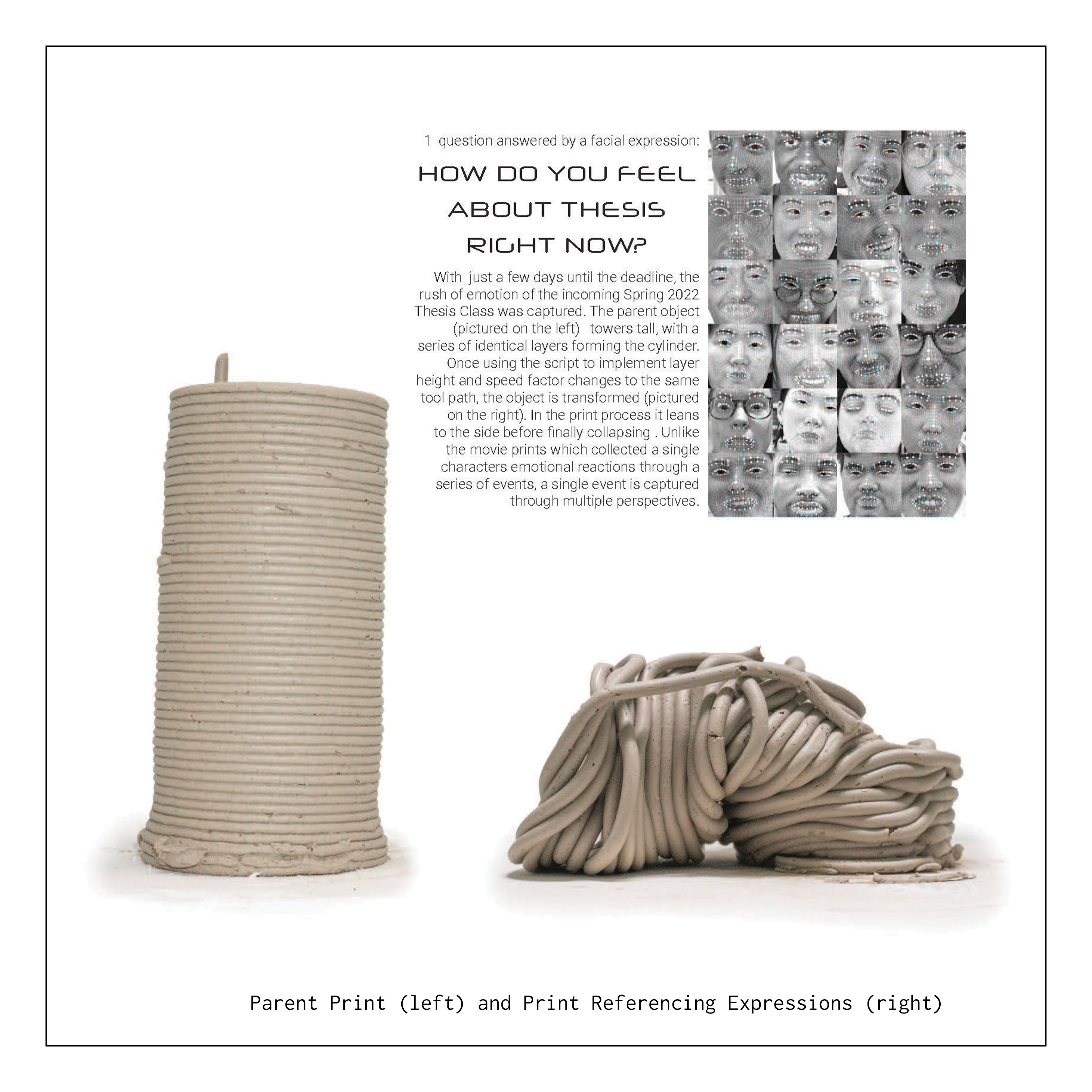

As mentioned, I used volunteers to test the system, asking each one to discuss their days. In the figures two the left, two volunteers are included as examples. I also used scenes from films/shows to exemplify my process, tracking the expressions of a character throughout the piece of media, creating wildly different prints for different genres.